Why Time Is the One Thing We All Seem to Crave

Why Time Is the One Thing We All Seem to Crave

Every day contains 86,400 seconds, but according to our Senior Content Writer, Mike Tuckerman, we still often feel like we don’t have enough time.

Here’s an interesting fact: the word ‘time’ is the most commonly used noun in the English language.

I only recently learned this in Dr. Rebecca Struthers’ new book, Hands of Time: A Watchmaker’s History of Time.

Struthers is a remarkable character.

Born and raised in working-class surroundings in England’s industrial heartland Birmingham, Struthers dropped out of high school and abandoned dreams of becoming a pathologist to take up a two-year goldsmithing course at Birmingham City University.

It was here that she met her now-husband Craig – and was introduced to horology, or the study of time – with Struthers becoming the first watchmaker in British history to hold a PhD in horology when she completed her doctorate in 2017.

Yet Struthers is so much more than a textbook academic.

Alongside Craig, she now runs Struthers Watchmakers in Birmingham’s historic Jewellery Quarter – where the couple create bespoke, hand-made watches designed with their own in-house movements that take years to complete and command a starting price of around $AU80,000.

A passionate educator and hands-on watchmaker in a vocation listed as ‘critically endangered’ by the Red List of Endangered Crafts, Struthers has made it her life’s work to educate the public on the finer points of watchmaking.

The Older I Get, the More I Think About Time

Why does it often feel like we never have enough time?

No matter how organised we try to be, or how many to-do lists we write, there rarely seem to be enough hours in the day to accomplish all the things we need to get done.

There’s always another meeting, always a new email to respond to – and that’s before we factor in all the things we need to do for the day that have nothing do with our jobs.

And all of these things are important.

When someone is asking for your time, it’s because they have things to do, too.

But I sometimes wonder if – before the advent of the internet and a digital culture that ensures our phones are never too far away – whether people felt like they had more time.

Perhaps it’s just a psychological thing.

But when the next ‘quick email’ or meeting request is just a notification away, it can sometimes feel like we’re being bombarded with more tasks than there is time to do them.

That’s probably why the concept of time and the way that we measure it is something I think deeply about these days.

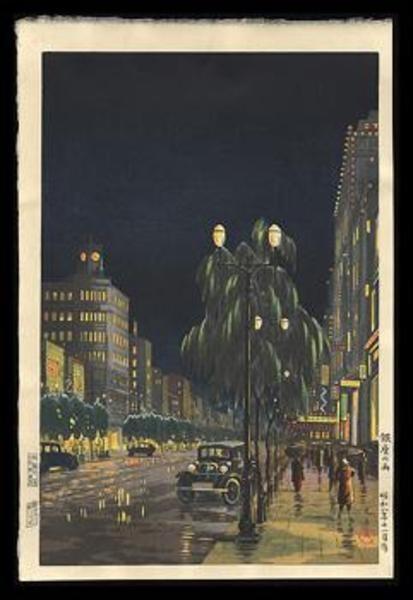

Rain in Ginza

On a cold December night in 2019, right before a global pandemic made international travel all but impossible, my wife Ashton and I took a car service from Narita Airport to Ginza in Tokyo.

It was pouring when we set off, and by the time we stepped out onto the main street of one of Tokyo’s most famous districts, the streets of a brooding night-time Ginza were slick with rain.

We could see our breath in the air as we turned the corner onto Chuo-dori, and I remember Ashton turning to me and saying: “I think you’ll own it one day”.

The ‘it’ in question was an extremely rare shin hanga – or ‘new print’ – by the largely forgotten Japanese woodblock print artist, Tsuchiya Koitsu.

It’s rare for a few reasons.

For one thing, Koitsu was never a particularly popular artist, even in his day. For another, the woodblocks were lost in a fire long ago – meaning this particular print can never be reproduced.

But perhaps the most striking thing about the print is its subject matter.

Known as ‘Ginza no ame’ in Japanese – and better known as ‘Rain in Ginza’ in English – it is, quite literally, a look down a rain-soaked Chuo-dori towards the legendary Wako department store.

Founded by one of the most visionary watchmakers in history, Kintarō Hattori, the Wako store is perhaps better known as the spiritual home of one of the world’s great watch brands, Seiko.

A Simple End to a Lengthy Search

I had asked my friend and experienced tour guide Yuka Yoshida to act as my buyer’s advocate on that trip to Tokyo, and for her to put me in front of a few people who knew the print.

The first person she connected me with was none other than the publisher’s grandson, Shoichiro Watanabe.

He owned a copy of the print himself and told me it held special meaning for him, as his first-ever job was in the Wako building.

He also told me he feared I’d never own the print myself.

I certainly didn’t find it on that trip to Japan. I’d been emailing dealers all over the world for years about Rain in Ginza – in London and Paris, San Francisco and New York, as well as in Tokyo – all to no avail.

But to cut a long story short, I do own the print.

After years of fruitless searching, one day I simply stumbled upon a copy for sale at auction from an online seller of Japanese woodblock prints in Chicago.

So I stayed up until 2am one Saturday night to place my bid – against many of the same dealers I’d spent years emailing – and one record price for a Koitsu print later, I was the new owner of a pristine copy of Rain in Ginza.

The One Thing Money Can’t Buy Is More Time

It took me just under four years to find an unfaded copy of Rain in Ginza.

But about six months before I landed my prized possession, I bought an entry-level Seiko Presage from its Cocktail Time series from Vintage Watch Co in Brisbane Arcade.

It was one of the cheapest watches they had, but I walked out of the store feeling like a million bucks.

Today, I sometimes hold the watch up against the backdrop of Rain in Ginza and the image of the Seiko building on the wall of my home office.

It invokes another time.

In the days before mobile phones and the internet, woodblock print artists like Tsuchiya Koitsu took their time designing eye-catching prints for the masses.

I was reminded of that in the first chapter of Dr Struthers’ book.

Lamenting the fact that the tight deadline she had set herself to complete a particularly complicated watch was about to fly by, like the geese above the forest on the edge of her cottage home in Staffordshire, Struthers points out that for all our desire to measure time with human-made devices like watches, the passage of time is still largely regulated by nature.

“I always find it comforting to remember that however mechanised and digitised our experience of time seems today, it will always be underpinned by natural forces that remain completely out of our control,” Struthers wrote.

“And that, in the end, some things take as long as they take.”

It took her another three years to complete the watch. I’ll remember that the next time I’ve got a looming deadline.

If you have some cool watch stories to share with me, or you’d just like a hand with your copy, drop me a line.

I love thinking about these sorts of things in my role as Senior Content Writer at Hunt & Hawk.